Gendercide Epidemic Ravages Indian Domestic Life

March 7, 2016

“I just strangled it soon after it was born. Why keep girls when raising them would be difficult?”

In this excerpt from the 2012 documentary It’s A Girl, an Indian woman describes a practice long endemic to the South Asian nation’s domestic culture: gendercide. As she motions to the spot where she presumably buried her newborn, it is revealed that she has killed eight of her own daughters.

In the many agrarian hubs of India, children are valued for their ability to work and generate income. Therefore, while sons can guarantee economic security through physical strength and dowries, daughters are seen as financial liabilities. Upon marriage, the bride is expected to pay a hefty dowry in the form of land or money to the groom’s family. This practice creates a severe financial burden on the bride’s family, who may be forced to sacrifice their entire livelihoods. And while the dowry is formally banned in India, many rural localities still practice the patrilineal custom. Its pervasiveness in India’s less-developed states has led many couples to kill their daughters as protection from the future financial hardship they may incur.

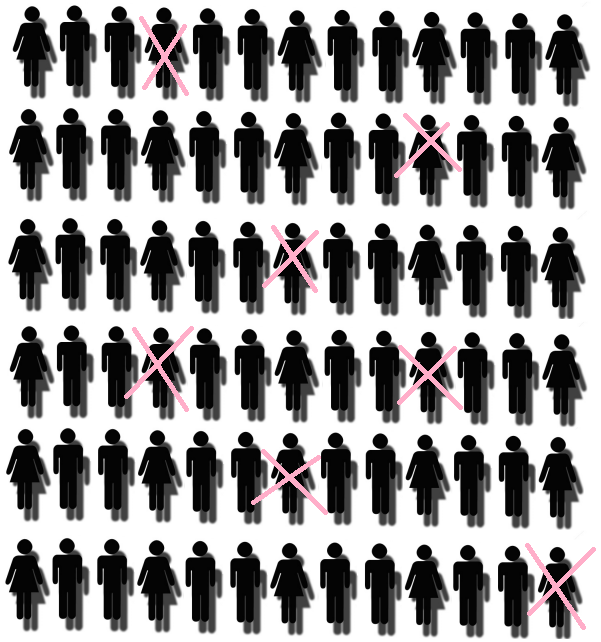

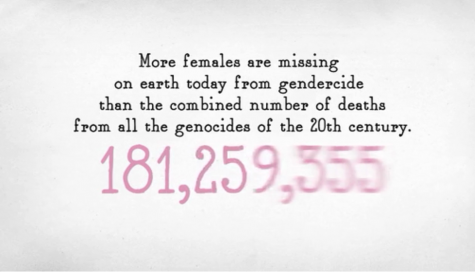

As the result of systemic gendercide, fifty million Indian girls and women have been killed in the last century. According to the Invisible Girl Project, this death toll runs higher than that of any other modern genocide.

Many of these deaths are attributed to sex-selective abortion, or feticide. The United Nations now estimates that 700,000 girls are aborted every year because of their gender, amounting to one abortion per minute in India. Though abortion is legal in India, sex-selective procedures are prohibited by the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act of 1994 (PCPNDT). Doctors are required to report all ultrasounds, and any who practice sex-selective abortions are subject to severe legal penalties. However, as many families pay physicians handsomely to conduct abortions off the books, the law is loosely enforced.

Indian families without access to ultrasound technology often choose to end their daughter’s life post-birth. Infanticide is so prevalent in regions throughout India—specifically, the northern provinces of Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand—that the mortality rate for girls ages one to five is 75 percent higher than that of boys in the same age group. Women who refuse to kill their daughters, or are unable to conceive a son, are often brutally abused and even killed by their husband and his family.

It is unacceptable that the Indian government is sitting by while girls and women are being systematically murdered by a patriarchal culture that economically disenfranchises them. Women and girls fulfill critical roles as leaders, innovators, mothers, and daughters in Indian society. Their potential must not be overlooked. The national government, in conjunction with community leadership, must enforce anti-feticide legislation with an iron fist. First, the PCPNDT should be strengthened. All doctors who practice illegal abortions must lose their license instead of merely paying a fee. Secondly, a third-party official vetted by the government must be present in major medical centers to monitor ultrasound procedures. This independent contractor would report violations of the PCPNDT to local and national authorities. Trained in domestic health services, he or she would keep a vigilant eye for spousal abuse and promptly report any suspicious interactions. Thirdly, social workers would monitor rural communities with high rates of feticide and infanticide. Placed in high-risk areas, they would educate men and women on the value of raising girls. This official would also be a liaison to the national and local court system, seeking justice for all victims of gendercide. Integrating national policy with grassroots leadership will promote a direct dialogue between local and federal officials, ensuring regional needs are properly communicated to the highest levels of government.

Under Prime Minister Modi’s leadership, India should follow neighboring China’s lead in providing monetary incentives to families who keep their daughters. China, with the highest rate of gendercide in the world, has improved its sex ratio from 121 to 116 males for every 100 female births through its Care for Girls program. Considering financial risk is largely at the heart of gendercide, poverty-stricken regions of India would respond well to a monetarily incentivized program. South Korea experienced similar success in balancing its gender disparity through a widely publicized crusade to uncover doctors who weren’t complying with anti-abortion laws. In conjunction with a national feticide awareness campaign and equal opportunity laws to promote education among women, South Korea saw a dramatic drop in infanticide and feticide.

However, change cannot come solely from the top. It must be galvanized from below as communities take concrete steps to reduce negative perceptions of women. Grassroots programs that empower women through education, vocational training, and micro-finance loans have a proven positive impact on such communities. In their book Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn describe women who fought for respect and change by establishing small businesses, hospitals, schools, and shelters to help benefit other women. Entrepreneurialism establishes women as decision-makers and breadwinners, granting them autonomy and economic clout. Subverting the stereotype of women as weak financial burdens is a crucial stepping-stone to ending gendercide.