Emerging Virus Spreads Across Brazil

Fũtbol fans from around the world massed in the Brazilian city of Natal in 2014 to watch that year’s World Cup. Unfortunately for Natal, the World Cup wasn’t the only major occurrence caused by that international congregation.

It was only a few weeks later that people started arriving at hospitals complaining of headaches, rashes, bloodshot eyes, and joint pain. Doctors initially suspected some kind of light Dengue fever, but blood tests soon made it clear that it was not Dengue or any other familiar illness found in Brazil.

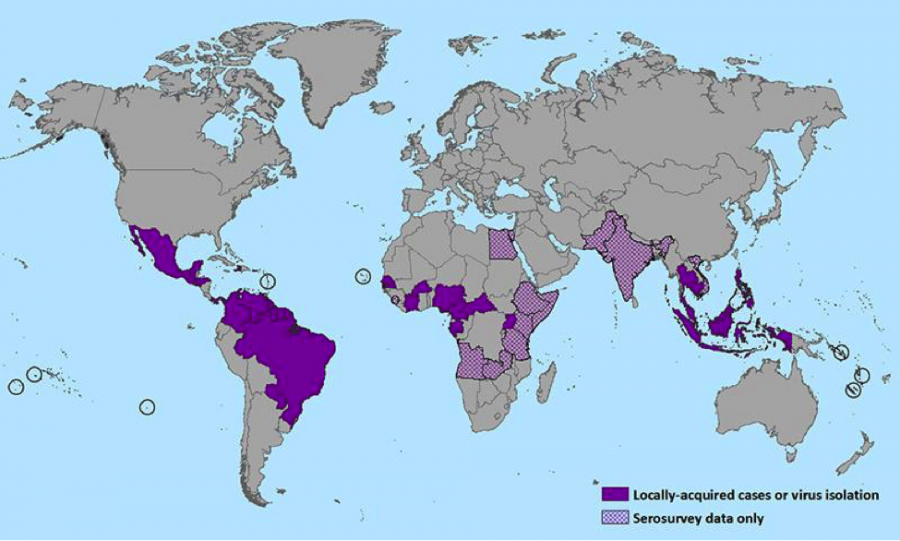

Researchers would later discover that this doença misteriosa, or mystery disease, was the Zika virus: A mosquito-spread virus originating in the Zika forest of Uganda that had been spreading among the islands of the Pacific. It is suspected that the virus was carried to Brazil by someone from one of the countries that contain the disease.

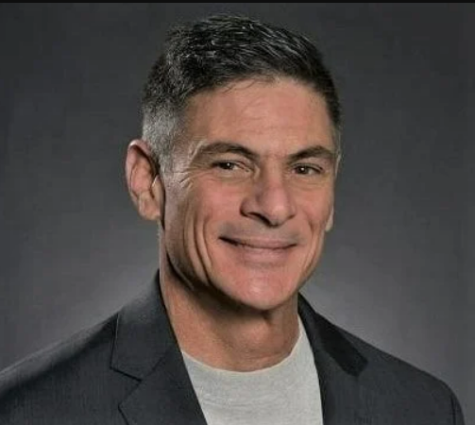

Following the initial cases of Zika in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Norte, the number of infected people continued to increase as the virus spread to neighboring states and the city of Salvador, which has a population of 2.5 million. Because federal reaction to this emerging epidemic was slow, it wasn’t until April of last year that the disease was identified by a virologist at the Federal University of Bahia in Salvador.

According to a statement he made in the New York Times, Dr. Soares was initially optimistic about his discovery. “I actually felt a sense of relief,” he said. “The literature said it was much less aggressive than viruses we already deal with in Brazil.”

Soon after, the Health Minister of Brazil, Dr. Arthur Chioro, released a statement that “Zika virus doesn’t worry us,” noting that there were many more deadly diseases in Brazil already that cause hundreds of deaths each year. However, physicians in the country and the international community were still concerned with the proliferation of this little-understood virus.

Cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a form of temporary paralysis, saw drastic increases in various cities in Brazil. One doctor in the city of Recife, Maria Brita, saw 50 Guillain-Barré syndrome patients last year — an increase of nearly 400% from the year previous.

Hospitals in afflicted areas also began seeing a surge of microcephaly in newborn children. Microcephaly is a birth defect causing a baby to be born with a head and brain smaller than usual. It can potentially cause still births or mental impairment in the developing child.

According to a CNN article, the World Health Organization has declared this emerging epidemic a “public health emergency of international concern.” The concern of the international community will certainly help to combat and contain this virus it may also cause unintended problems.

An article by Reuters claims that 41% of Americans who have heard of the virus have stated that they are less likely to go on vacation to afflicted areas because of it. Although there have been no signs of a decrease in tourism yet, the tourism market in South America may still suffer as news of Zika spreads.

Zika has already affected American tourism in that there have been a number of travelers who have contracted the disease. It seems likely that these won’t be the only instances of the disease in America. These concerns raise the question: What should America do in response to this outbreak? And how should we prepare for the few outbreaks that will inevitably happen here?